Let's talk about selective mutism! No, it's not a superpower or a cool magic trick, but it is an important anxiety disorder that affects some kiddos that's worth discussing. Picture this: at home, they're chatty Cathy, but put them in a social setting like school or a playdate, and all of a sudden, they're as quiet as a mouse. It's not because they don't want to talk or because they're being stubborn. Nope, it's due to anxiety, which can make talking in front of others feel like a big scary monster. But fear not, there are ways to help these little ones find their voice and be brave talkers, like Parent Child Interaction Therapy for SM (PCIT-SM). Plus, there are tons of resources out there, like the Selective Mutism Association, and even a Facebook Group for parents dealing with SM. So, let's get chatty about selective mutism!

Can you give us a brief introduction to what selective mutism and how it differs from other communication disorders?

Selective Mutism is an anxiety disorder. Children with SM speak at home an often are quite chatty there. However, in places like school, with friends or other adults and even extended family, they may not speak at all or to a much lesser extent. Unlike other communication disorders, which are problems related to the speech itself, SM is due to anxiety.

In your experience as a clinical psychologist, what are some common misconceptions about selective mutism?

There are a lot of misconceptions, unfortunately, which is why I am so glad we are able to dispel those myths here. One is that the child who is not talking is being “defiant” or “willful.” This is not the case. Children with SM often really want to talk and feel like they can’t. Another common myth is that SM us due to trauma. While children do certainly experience trauma, SM is not generally thought of as being a result of trauma. Finally, people often think that the child will just “grow out of it.” Kids with anxiety disorders don’t tend to just grow out of it. Intervention is the best way to address SM and other anxiety disorders.

Can you discuss the possible causes of selective mutism, and is there any genetic predisposition or environmental factors that play a significant role in its development?

Like most mental health disorders, SM likely develops as a product of nature and nature. This means that there may be a genetic predisposition to some anxiety somewhere in the family tree. However, a powerful reason that SM is maintained is in the environment. Very wonderful and well intended adults (and kids) often remove the expectation to speak for the child, in an effort to make those distressing feelings go away. Over time, kids with SM practice “not talking” and get better at it. To illustrate- a parent might go to a store and a clerk, trying to be friendly says, “Hi. What’s your name?” The child with SM might look at the parent, look away or start hiding. The clerk doesn’t want to make the child feel uncomfortable and neither does the parent. One of the adults might say, “That’s OK, they're shy” and the adults move away from the question. As a result, the expectation to speak has been removed.

How does selective mutism typically manifest in children, and what are some key signs or symptoms that parents, teachers, or caregivers should look out for?

When children do not talk in settings like school, on playdates and with extended family that is a sign. The lack of talking lasts for at least a month and does not exclusively occur in the first month of school. I often hear that the school has asked the parent, “Does your child talk” and the parent is shocked because the child talks a lot at home. Another sign may be avoidance of interacting with peers verbally, even when the child has expressed that they like the peer, wants to play and knows the peer.

What are the long-term consequences of selective mutism if left untreated, and how might it impact a child's development?

Untreated anxiety disorders in general can lead to worsening of anxiety and also the occurrence of other anxiety disorders or depression. More broadly, if a child is not able to talk in school, it makes it near impossible to assess their abilities. If a child cannot connect with peers, their social development may be negatively impacted.

What's the process of diagnosing selective mutism, and what role do mental health professionals, such as yourself, play in this process?

Not all mental health providers are familiar with SM. Finding a psychologist or other mental health provider who knows child anxiety well is a good start. Doing a comprehensive evaluation that involves the caregivers sharing information about the child’s social and academic development, along with observations about their behavior, mood and anxiety is important. Getting a very clear understanding of where the child speaks and struggles to speak is key. Finally, many SM experts have a special way of evaluating the child without putting direct pressure on the child. For example- I do a parent- child observation where I can observe the child talking and playing with the parent before introducing a new adult.

What are some effective treatment strategies for selective mutism, and how do you determine which approach would be best for each individual child?

Evidence-based treatment is important and there are some treatments that are supported for SM. I am trained in Parent Child Interaction Therapy for SM (PCIT-SM), which is a treatment that teaches caregivers skills to help their child with their brave talking. Treatment needs to balance creating comfort with the child and also prompting the child for speech. Often this starts by helping the parent elicit and reinforce their child’s speaking and then ‘fading in” new speaking partners, which is the process of transferring speech to new people. Treatment is very active, with caregivers doing a lot of out of session exposures (or brave talking practice).

How can parents, teachers, and caregivers support a child with selective mutism, both in and out of the therapeutic setting?

One important first step is to become educated about SM and how to work collaboratively as a team (caregiver- child-school). Another important step is to collaborate with a treatment provider when there is one and connect with organizations that provide information and material about SM (e.g. Selective Mutism Association or SMA). It’s important to be patient- many caregivers and schools really want to help the child and can forget that making gains takes time.

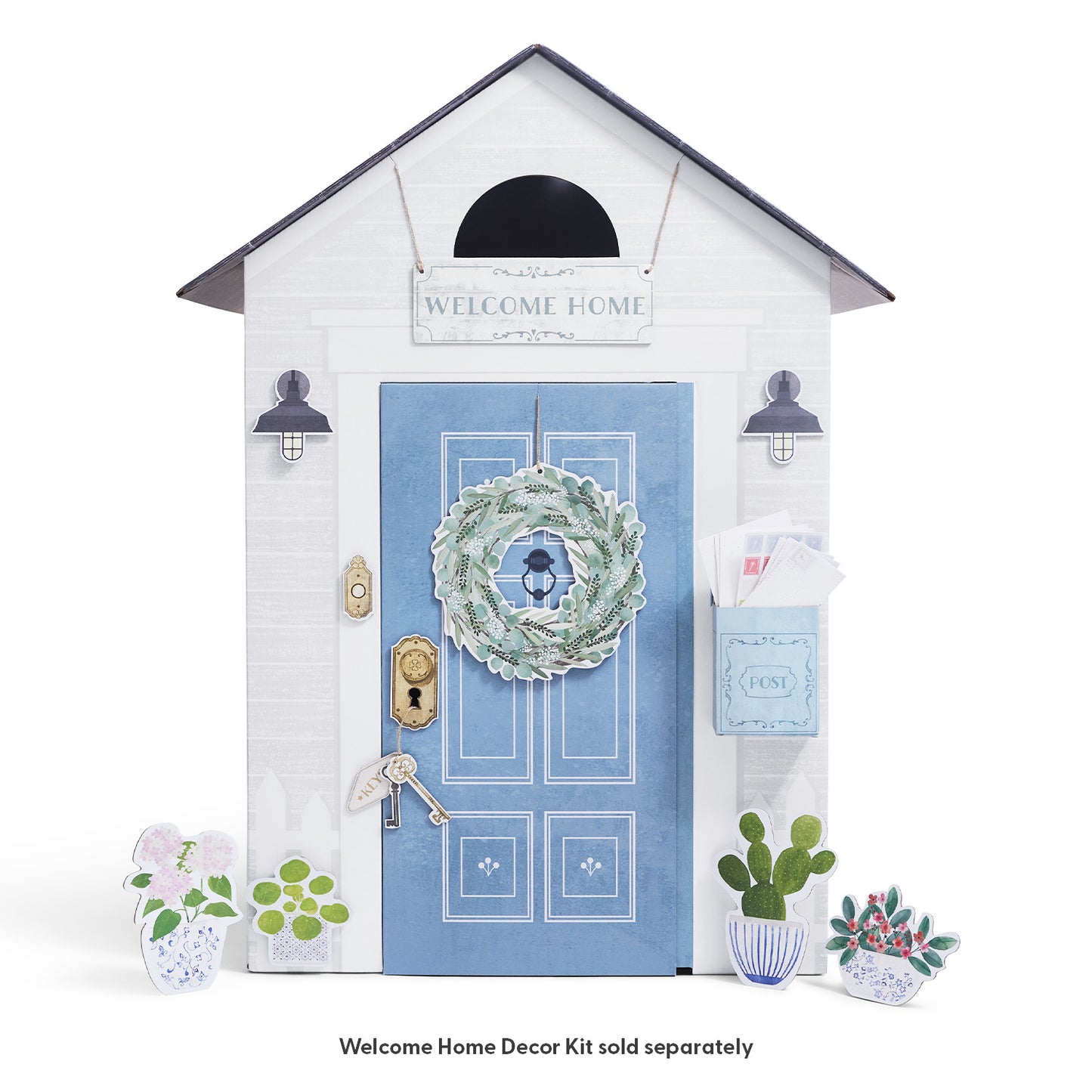

What's Fade In practice and how can a playhouse be helpful?

During the fade in process, a caregiver is helping a child speak to a new adult or peer. If the child is comfortable in their own home and playing in a space and with toys they enjoy, this can make the process easier. A fade in shouldn’t feel “formal” - rather it should be playful and fun. The more comfortable the child is, the more likely they are to talk first with their parent and then in front of a new person.

When a caregiver is working to help a child with SM talk to a new peer, being playful is important. Parents sometimes struggle to find games and activities that will facilitate talking and interacting. Often, we ask parents to have a playdate in their own home, as this is where the child is most comfortable. If a child has toys and play spaces that they love, this is a natural place to invite the peer to join. With the parent using brave talking skills, they can help the two children start interacting and speaking.

Any resources you would recommend for families dealing with selective mutism?

SMA (Selective Mutism Association or SMA) has a great website and also video library that provides great information and materials. They also offer a support group.

There is an active Facebook Group - Parents of Children with Selective Mutism which has been a support to many.

Dr Rachel Busman is the Senior Director of the Child & Adolescent Anxiety and Related Disorders Program at Cognitive & Behavioral Consultants in NY. She developed and runs Voices Rising, an intensive therapy program for children with SM. She is a past president of the Selective Mutism Association and is certified in Parent Child Interaction Therapy for SM. Most recently, she authored a book called Being Brave- with Selective Mutism: A Step By Step Guide for Children and Their Caregivers. You can contact Dr. Busman at sm@cbc-psychology.com.